Tula was the leader of the great slave revolt of 1795 in Curaçao. What do we know about Tula?

Tula bore the nickname of "Rigaud," named after the Haitian General Benoit Joseph Rigaud, one of the heroes of the Haitian revolution.

It is not known where Tula came from, but he was well aware of the situation in Haiti, where a slave revolt led by Toussaint had taken over the Colonial regime. He was aware of the French Revolution and the revolutionary ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity. He knew that the French revolutionary regime had occupied a large part of Europe and that this regime wanted to abolish slavery in the French colonies. Among the insurgents a letter from General Rigaud was cited, in which freedom was promised to all slaves in all countries which were under French rule. Now that the Netherlands was placed under French rule (1795-1801), it was Tula's conviction that slavery would soon be abolished here, in Curaçao, as well.

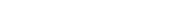

Tula was a slave field worker on plantation “Knip,” owned by Casper Lodewijk van Uijtrecht. Little is known about Tula’s personal life, not even from official documents that have been preserved. Reverend Bosch, who arrived in Curaçao in 1816, wrote that he had spoken to people that had personally known Tula. They recalled him as articulate and a man of great stature.

Father Jacobus Schinck, who was sent during the revolt in 1795 by the colonial government as a mediator to meet with the rebellious slaves, is the only one who had spoken with Tula and whose recordings are preserved in the government archives. His account starts on 19 August when he spoke with Captain Tula at Plantation house “Porto Mari” at half past eight in the evening.

"We have been abused too much, we do not seek to harm anyone, and we are just seeking our freedom. French Negroes gained their freedom, Holland was occupied by the French, then we must be free here"

These are Tula's words, recorded by reverend Schinck. He continues:

"Sir, Father, do not all the people stem from a common father Adam and Eve? Did I do wrong by releasing 22 of my brothers from their confinement, which they were unjustly thrown into? French freedom has served us as a torment. When one of us was punished, they constantly invoked against us, "Do you seek your freedom as well?" Once I was tied. I cried incessantly ‘mercy for a poor slave.’ When I was finally released, blood ran out of my mouth. I fell on my knees and cried out ‘Oh God Almighty is it your will that we are so mistreated?’ Ah, Father, even an animal is treated better than us. If an animal has a broken leg, it is taken care of." (A.F. Paula, 1795 de Slavenopstand op Curaçao, 269).

As Father Schinck conveyed the proposals of the government to Tula, Mr. van der Grijp, a horseman captured by the rebels, heard the rebels say in French "Le curé vient ici pour nous cajoler" (The priest comes here to flatter us). Schinck also heard the rebels softly singing French revolutionary songs at night.